How is the Internet Changing Your Brain?

Are you a voracious reader? Are you the kind of person who finishes one book a week? And, in an average week, can you say you spend at least half as much time reading your books as you do connected to the Internet?

If you answered yes, you’re one of an increasingly rare breed. By 2008, the average amount of time Americans over the age of 14 spent reading printed material was about 143 minutes per week, a decrease of 11 per cent in just four years.

Embarrassing Admission

Nicholas Carr, an experienced author and columnist, admits that he is finding it more and more difficult to employ the sustained concentration necessary to finish a book. He has written The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains in an attempt to understand how the neuro-circuitry of the average Internet user’s brain has changed over many years of adaptation to the technology.

I’m a former librarian who was an English major for my bachelor’s degree. Many years ago, I was a devotee of Thomas Hardy’s work, and thinking that I’d like to go back to some of the happiest times ever spent with my nose in a book, I tried to reread, appropriately enough, The Return of the Native. Sadly, I found Hardy’s prose unreadable.

I’m a Baby Boomer and so is Nicholas Carr. If you’re reading this and you’re a Millennial, you may not relate to many of the ideas summarized here. To use an analogy, you don’t know what salty foods really taste like unless you’ve experienced the absence of salt for a long time. And most Millennials have spent most of their lives connected to the Internet as their main source of information. They don’t know anything else.

Some Background

In his book, Carr first gives us some background on the scientific studies and live experiments which proved neuroplasticity – that is, the ability of the human brain to adapt to its environment as it creates new synapses and neural pathways. He then uses that fact to take us on a tour of history using some fascinating exposition on how human society changed with the introduction of new tools like the map and the clock.

And then Carr gives us a lecture on the history of literacy. Reading was originally a group activity, where someone always read aloud. Even in privacy, individuals still sounded out the words, due to the limitations of early text. But as the printing press made books ubiquitous, human beings began to read silently. Reading became an act of personal reflection and a time to expand the imagination. For the truly appreciative, reading became a conduit for the worship of language.

We should not imagine that learning to read written text came easily to anyone. As Carr points out, the brains of each reader had to learn to concentrate for sustained periods of time. It took some time for humans to make the transition from an oral culture, which relied on stored memories, to a written culture, where you could find just about any idea in your collection, or the library’s collection, of books.

The Development of Our Age

For centuries, this was the only model for society. But, enter the digital age. First, the personal computer, then the Internet. And finally, the World Wide Web and the rapid expansion of the Internet into every corner of life.

As web page design evolved and bandwidth expanded, webmasters began to increasingly incorporate hyperlinks on web sites. Nobody was content with that addition, so in very short order, designers added multimedia to web sites. It seemed that you could never get a web page to look busy enough.

But as Carr points out, content on the web is created to be distracting. Your brain deals with a lot as you surf the web, and with enough time, your pre-frontal cortex becomes exhausted as you navigate pages and evaluate hyperlinks. It’s cognitive overload for your nervous system. And web use does not contribute to knowledge retention nor deep thinking. Further studies have confirmed that a multimedia experience does not help us learn better. After all, how much are students getting out of a lecture if they are texting and tweeting during the presentation?

A Few Useful Things

At this point, you’re probably wondering how the information in The Shallows could be practical for you.

Well, Carr summarizes what we’ve learned from research, especially from the findings of Jakob Nielsen, who has studied online reading since the 1990’s.

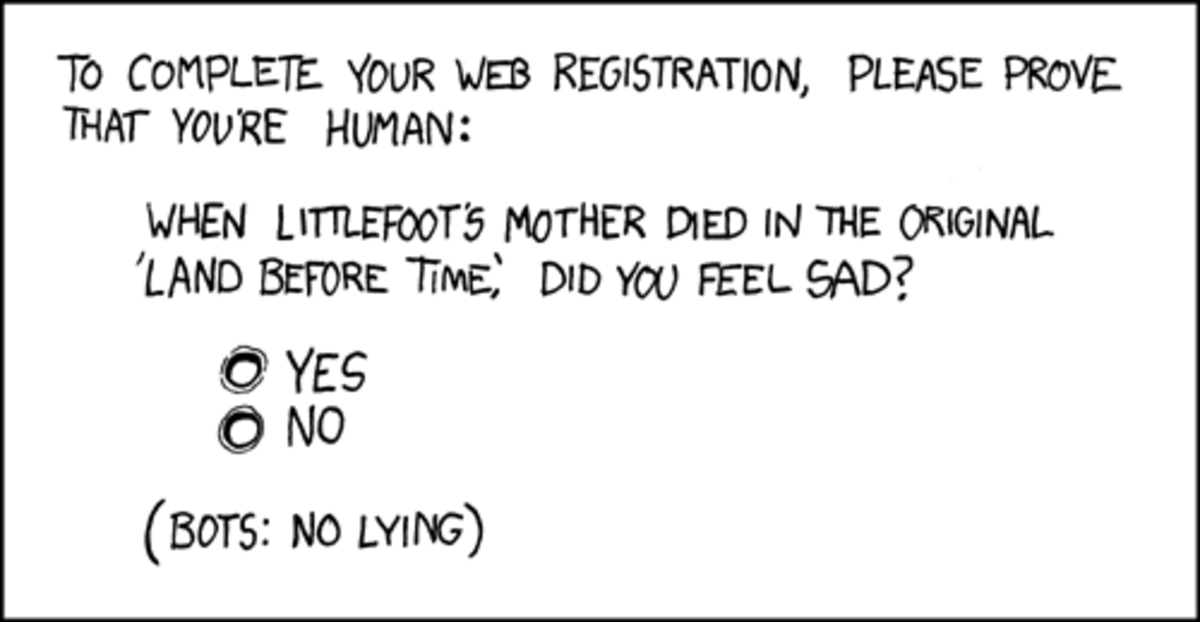

Using eye-tracking studies, Nielsen measured how web users browse web content. Very few of the participants read text slowly and line-by-line as you’d read a book. Here’s how the typical user’s eyes moved:

- Glance all the way across the first two or three lines of text.

- Let the eyes drop, and scan about halfway across another few lines.

- Let the eyes drift a little farther down the left-hand side of the page.

In short, the eye movement pattern resembled the letter “F”.

And, as other researchers confirmed, the average amount of time a user spends on a web page is ten seconds. Fewer than one in ten page views last longer than two minutes.

So, are web users actually reading this hub to its conclusion? No.

Google has its own team of researchers, and I believe they knew all of this information before the studies were published. Google uses reader behavior to maximize the placement of its ads. If you’d be successful making money on HubPages, you’ll design the first few paragraphs of your articles to conform to proven reading and scanning patterns!

Google -- Science, not Art

Google, incorporated in 2000, is a company dedicated to quantifying, measuring, and analyzing. Despite what you see with the cute seasonal variations on the Google search page, Google does not care about what looks good. They’re only interested in how their pages perform, and the amount of value they bring to a searcher, which not coincidentally, tends to bring impressive revenues to their company.

And, as Carr points out, Google is determined to make profound changes to the idea of literacy and book learning. Perhaps you use Google Books. Perhaps you’ve heard of the lawsuits that have been brought against Google, after Google decided to scan millions of out-of-print books that had not yet made it to the public domain.

As Google digitizes more books, it effectively creates a giant database that can be mined. Thus, reading becomes more fragmented and less coherent. Did you know that Google has a cut and paste tool which conveniently allows you to lift out relevant passages from public domain books and place them on your web page? And they’ll continue to milk the technology to create new tools.

As Carr says, in regard to Google’s ambitious attempts,

The strip-mining of relevant content replaces the slow excavation of meaning.

And What About the Book?

All of this is here now, and more is expected. The Kindle e-reader has been around for only three years, but already it has revolutionized the reader’s approach to a book. It’s too soon to give a proper evaluation, but there is every reason to believe that companies will focus on making book reading a highly interactive activity.

The respect shown to a book – that is, the tradition of regarding a book as a completed work that needs no revision – will someday become a quaint sensibility.

That’s the crux of the matter. As we spend more and more time online, our ability to evaluate, ponder, and make sense of what we read is going to suffer. We will become habituated to a way of being that could never have been imagined by the developers of the microchip.

Is There Any Respite?

Carr cites studies showing how even a brief time spent away from digital life, communing with nature in a quiet setting, re-charges the brain and allows it to rest from the constant heightened activity spent online. Although he didn’t mention it, exercise brings many physical and mental benefits that web surfing and computer gaming do not.

And, yes, sitting and reading a book is also an excellent way to quiet the mind and allow it to reflect on the deeper meanings contained within the pages of text.

Recommendation

I recommend Carr’s book. If you don’t mind wading through the summaries of current research in neuropsychology, you’ll find a lot to ponder in The Shallows. Carr has used the Internet longer than most of his readers, and he writes a completely sympathetic book for those of us who live much of our life online.

If you need a historical perspective on how humankind adapted to new tools, and how our experience of the Internet is changing the way that we learn, this is your book, and you’ll no doubt find plenty of fodder for a book discussion group.

On the other hand, if you want some interesting insights into how users interact with web content, you can skim the background material, and concentrate on learning about trends that may help maximize your web publishing efforts.

If you’re (in the words of Sven Birkerts, who wrote The Gutenberg Elegies) “a poor person, a Luddite, or a refusenik”, The Shallows will confirm your worst impressions about the encroachment of technology into modern life.

And if you are, like my best friend, an Internet newbie, you’ll find in this book a prediction of the likely course of your personal neural circuitry over the next few years.

Forearmed is forewarned.

Image/Photo Credits

Image of a woman web surfing from sultry

Photo of a book stack from miss_yasmina